Your ancestors were inbreeders. So were mine.

That's mostly okay. We are all far more closely related than you might expect.

When writing about evolution, writers often begin by reminding our reader that they are an evolutionary success. That they come from an unbroken lineage of successful ancestors. How could it be otherwise? You had a mother and a father. At least biologically, you did. Your parents each had a mother and father of their own. And that same mundane pattern stretches all the way back to the first sexually reproducing single-celled creatures about 2 billion years ago.

Before that, of course, there were the asexually reproducing ancestors, again a consistent series of evolutionary success stories, but with one parent in every generation, rather than two.

If “you are an evolutionary success story” sounds like the first layer in a crap sandwich, you’re not entirely wrong. On top of the affirming news about your ancestors’ success, I will layer the bad news: those same ancestors were all inbreeders.

Before you take exception, I should note that I’m not talking about incest as we currently understand it. Although that happened from time to time. But, if we trace any family tree back far enough, some characters will appear in multiple places, like extras popping up in different costumes playing different minor roles.

Numbers game

Each of us has two biological parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents and so forth. The number in each generation doubles, which very quickly leads to some very large numbers of ancestors.

For the sake of convenience, I will assume each generation averaged 30 years from a parent’s birth to that of a child. That is to say, the average parent was 30 when the average baby was born. That may be a bit conservative; our ancestors mostly had their first kids when they were still in their teens. But some children were born to far older parents.

So if we traced the ancestry of a baby born in 2025 back 300 years, to 1725, we would expect to find 1024 unique ancestors. Wikipedia tells me that in 1725, Catherine the Great had just ascended to the throne in Russia, Johan Sebastian Bach was churning out some of his greatest hits, and Casanova was born.

A thousand or so distinct individuals who lived at roughly that time doesn’t stretch the imagination. Especially since, of course, the 512 matings between those 1024 individuals would have happened in many different towns or even continents, and could have happened over span of decades. The past looks chaotic when you look back at it in this way.

Things get a lot more complicated if you look back 900 years, or roughly 30 generations. Now we are talking about over a billion ancestors (1,073,741,824 to be precise). That’s where the conversation gets awkward. The human population in the year 925 was only around 270 million.

At the start of the Common Era, the worldwide human population is estimated to have been between 200 and 300 million people. And yet if every ancestor of yours appeared only once in your family tree, you would have roughly 3 times 10 to the power 20 ancestors who lived at the time of Augustus, Herod and Jesus.

That number is quite literally astronomic. Like when Brian Cox goes gaga over the 100 billion stars in the Milky Way, we are still talking about a number 3,480,000,000,000,000,000,000 times bigger than that. I don’t want you to stare at that number too long, both because I might have made an error somewhere and because looking at those kinds of numbers sends physicists into an existential tailspin. I don’t want that to happen to you. At least until you have shared this article.

Pedigree collapse

You are going to have to accept that you could never have had that many unique ancestors. Some ancestors count multiple times in any pedigree. Evolutionary geneticists call this phenomenon “pedigree collapse,” and even a single instance can make the number of different ancestors in any generation a lot smaller. For example, if a person’s parents were first cousins, they would have 6 unique grandparents and 12 great-grandparents, compared to 8 and 16 if their parents were unrelated.

“Unrelated” is doing some heavy lifting there. When you go back enough generations, everybody has these kinds of matings between relatives in their pedigree. Sibling or cousin matings are the attention-grabbers, but far more numerous are matings between more distant relatives. Usually, these kinds of matings are not recognised as inbreeding because after a few generations, each with some people moving to a new town or country, people have no idea they are distantly related. The less people move during their lifetimes, and the more they are isolated from other communities, the greater the overlap in ancestry.

Why does inbreeding have a bad reputation?

Breeding between close relatives, like siblings and cousins, can lead to health problems in the offspring. That’s because the chances of inheriting identical copies (alleles) of a given gene are vastly higher when both parents share the same ancestor. Many alleles that have ill effects are both rare, and recessive. Recessive means they only affect development in individuals with two copies.

So there are good reasons to find a mate that you are confident is unrelated. One generation of outbreeding removes (most of) the risk of your children having rare recessive genetic disorders. But if they inbreed, their children could suffer ill effects.

While outbreeding is a good option in genetic terms, it has social implications that can become complicated by wealth and power. An ever-expanding number of relatives can create tensions over property and succession. Every now and then, a society has the bright idea of limiting these risks by keeping marriage in-house.

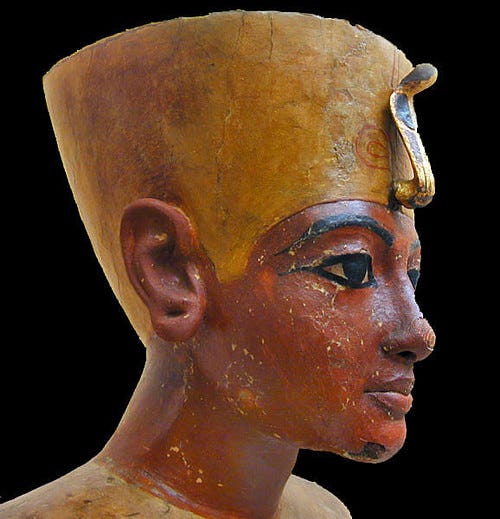

This happened at various times in ancient Egypt. Tutankhamun, the young king whose unlooted tomb was found and opened in 1922, is thought to have died of malaria and the effects of a broken leg. Skeletal problems in his spine, feet and legs suggest a history of inbreeding, borne out by the fact that his father, Akhenaten and his mother were likely siblings. Tutankhamun’s wife was either a sister or half-sister, so perhaps it was unsurprising that neither of her two pregnancies ran to term.

European royal families showed an occasional proclivity for inbreeding. The mighty Habsburgs regularly married cousins to one another, or uncles to nieces. Charles II had only 32 of a possible 64 great-great-great grandparents. He was also frail throughout his 39 years of life, and sported a particularly prominent jawline characteristic of many Habsburgs.

The better news

Most pedigree collapse is not due to tight inbreeding. Instead, it is due to the appearance of some prolific ancestors, from whom almost everyone in an area descends. This can happen when a new gene arises that makes individuals who inherit it surprisingly fit.

For example, the Black Death killed a staggering number of people, especially in north Africa and Eurasia. In the 14th Century alone, it killed up to half of the human population in Europe. Any gene that helped individuals avoid or fight off infection from the flea-borne Yersinia pestis bacteria would have been favoured by natural selection for as long as the disease remained common. And that seems to be exactly what happened with an allele (version of a gene) called the C-allele of the gene rs2549794.

Studies of ancient DNA from people buried in cemeteries in Denmark and London before versus after the great plague of 1348-50, as well as from a London plague cemetery used in 1348-9, showed a massive jump in the frequency of the C-allele. Having two copies conferred about 40 per cent higher chance of surviving an infection.

The person who first had the tiny mutation that created the “C” form of rs2549794 did not live in 14th-century Europe. The allele was already moderately common by then, benefiting from enhanced immune responses to a variety of respiratory infections*1. The allele was, on average, advantageous in a time of extensive infectious disease, and became dramatically more so due to natural selection in the waves of Black Death from the 14th-century onward.

If you inherited this version of the gene, then the person in whom the gene first arose as a mutation was (at least once) your ancestor and the ancestor of all other people with the gene. If you have two copies of the gene, they were your ancestor at least twice. Those are very conservative estimates, but the shuffling of genes each time a sperm or egg is made mean that one may have inherited no other genes directly from that person.

Massive selection events like the Black Death are rare, but even far less dramatic events can lead to selection. And selection inevitably causes pedigree collapse as a mere mathematical consequence. The signature of inbreeding in all of our ancestries is a signature of evolution by natural selection.

Let me finish with another kind of pedigree collapse due to a different kind of selection. This one comes from the occasional person who dominates history and sires plenty of offspring in the process. History has been kind to many such figures because, to mangle Winston Churchill for a moment, they are the ones who wrote – or at least created – history.

The most famous example is Genghis Khan. He and his brothers and sons established the largest contiguous empire that history has ever known. And, by lucky accident, they carried a distinctive Y-chromosome, so we can tell today which men descend from Khan (or at least his paternal grandfather) in an unbroken male-to-male lineage.

For the full story of Khan’s genetic legacy, and those of several other highly successful male ancestors, check out my post from 2015, which I updated for Substack earlier this week.

The answer, in the case of Genghis Khan? About 1 in 200 men alive today descend on a strictly male line from the Great Khan. Talk about a superancestor! Talk about pedigree collapse!

The C-allele of rs2549794 is implicated in several autoimmune diseases like Crohn’s. It is likely the allele did not replace all other alleles because of the autoimmune downsides, and one might expect it to become less frequent if respiratory infections remain low.

Just came across this cool animated map tracing the ancestry of one person (the map-maker's daughter) over from 1615-2025. It traces 4000 ancestors, marked with different colours for her maternal and paternal ancestors, and those ancestors that contributed to both sides of her pedigree. A very neat illustration of just how fast one's number of ancestors racks up, and of pedigree collapse. A nice compliment to my post on how our ancestors were inbreeders.

https://brilliantmaps.com/4000-ancestors/