Is the gender equality paradox real?

A new look at old evidence suggests that the tendency for sex differences to get bigger when gender gaps close might be a case of "Simpson's paradox".

Where do behavioural differences between women and men come from? Few questions in the behavioural sciences generate more heat in everyday life, intellectual discourse, and politics.

The heat radiates from friction between two opposing intuitions, each strongly held. That sex differences are innate, or that they come from experience. The same opposing intuitions animate all questions about how behaviour arises: biology versus socialisation, nature versus nurture, genes versus environment. The ancient Greeks had their own version of this polarity, and so has every society before or since.

Even the most cursory understanding of how traits develop, followed by a moment’s thought, leads to the conclusion that we can never fully dismiss one side or the other. Traits develop, and that entails environment / nurture / socialisation acting on evolved, biological substrate. And yet here we are, happily ensconced in our own side of what Steven Pinker called “The Last Wall Standing in the Landscape of Knowledge”.

When one considers what can be done about wicked societal problems, all nuance is lost. How many worthy education campaigns have foundered because their authors staked everything on a faith in human capacities to learn whatever it is we want to teach, or in a simple idea that redressing inequities will reverse their (putative) effects? And how many other worthy interventions never gained support due to pessimism about a fixed human nature?

The opposing reflexes often amount to heaping all blame on either the system or the victim. You would think that with the best of 21st Century science at our fingertips, we might come up with better ways to understand the complexities of human behaviour and the problems people face? Well, we have, but they are neither as pithy nor as intuitive as the divisions that keep the Last Wall standing.

Sex differences, gender differences

Sex differences are present in many human traits. By “sex differences” I mean that in many of the traits that have been measured, samples of adult females differ, on average, from samples of adult males. Some papers in this area concern “gender differences”. That is, differences between women and men. Sometimes there is a specific intention to study gender rather than sex, or the reverse. Sometimes, studies merely conflate sex and gender. The area is complicated, and if you’re interested, I have written about the issues involved and the problem of gravitating to “gender” because it sounds more wholesome or inclusive than sex, even when what one really means is sex.

For this article, I am going to blaze away with sex differences, and maybe lapse inadvertently (we all do it) into “gender”.

Argue as people do about the causes of sex differences, their existence is an empirical reality. Male-female differences are observed in a vast number of measures of personality, emotions, behaviour, cognitive performance, and attitudes. In most of these traits, the sexes overlap. It is the averages, or as statisticians know them, the group means that differ. It should also go without saying that one cannot infer much about an individual’s attributes from the averages of those attributes among members of their sex.

I would really rather not take any more pains to convince you that sex differences exist. But if you like,

, one of my favourite substackers and authors, writes about them often in his Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter. His discussions are interesting, and nuanced, and avoid the trap of encamping on one side of the Last Wall, and throwing grenades at the other.Among those who do go in for Last Wall thinking, the argument is that sex differences evolved because – in our evolutionary past – the attributes that made successful fathers differ from those that created successful mothers. While the evidence of consistent differences across cultures accords with this account, retrofitting an adaptive explanation to what we observe in the world today is often lazy. Such retrofitting usually tells us more about the biases of the retrofitter than anything else.

The fact that the magnitude of many sex differences varies considerably among cultures suggests that much more is involved than simple evolved strategies. Here, the social scientists, often more comfortable on the nurture/experience side of the Last Wall come into their own. Sex differences, according to their view, arise when males and females are socialised into different roles, with different access to power, having different kinds of experiences as they move through the world.

So far, so sensible.

Nurture-heavy views also come with a prediction. In 2004, Alice H. Eagly, Wendy Wood and Mary Johannesen-Schmidt, prominent proponents of the importance of socialisation into sex roles, predicted that moves toward gender equality would diminish the differences between sex roles, and thus erode many sex differences, perhaps even leading to their “demise”.

A paradox

The idea gels with both scientific theory and lay-person intuition about sex and gender. But it is the testability of the predictions that represents the idea’s greatest strength. Testable predictions are the ore from which scientific progress is mined.

So, in 2015, evolutionary psychologist David P. Schmitt tested the prediction. He looked at 28 traits for which cross-cultural data, and measures of gender equality and ideology concerning sex roles were available.

In brief, the results did not uphold the social role theory. Quite the opposite. Only in two out of 28 traits did sex differences narrow as gender equality increased. In six traits, the sex difference remained stable, and in the overwhelming majority – 20 traits – sex differences were larger in places with more equality between women and men.

I wrote about his findings at the time, and provided the following illustration from the results on personality traits:

For example, women tend to score higher than men on personality tests for extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Gender equity tends to elevate all three of these traits, but it does so more in women, widening the average sex difference.

This effect came to be known as the “gender equality paradox”. It is not really a paradox (is anything?), but rather a surprising counterintuitive finding that, as social and structural conditions become more equitable, sex differences in all manner of other traits get bigger.

Replications

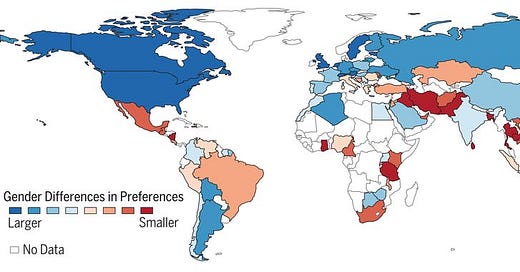

On its own, such a result might be dismissed as merely curious. But a slew of similar findings followed. One particularly impressive study, published in the uber-prestigious journal Science by economists Armin Falk and Johannes Hermle, involved 80,000 participants across 76 countries. They used games that economists have developed to measure “preferences” (which is how economists describe what psychologists often call “traits”). The preferences include participant inclination to take risks, exercise patience, behave altruistically, trust others and reciprocate with other players. In countries where women and men experience more similar opportunities, the more different their preferences.

What to make of this surprising, but now apparently robust finding? The authors seem to converge on the interpretation that places where gender equality is highest tend also to be places where it is easier to obtain the material necessities for living. Note the right-side panels of the figure above, in which Falk and Hermle show that gender differences grow bigger with both gender equality and economic development.

When freed from low economic development and/or steep gender inequalities, women and men are not as constrained in their behaviours and preferences. Thus freed, women and men can pursue their individual interests and preferences. That includes sex-specific interests and preferences with ostensibly deep evolutionary roots.

I’m sure you can see why the idea of the “gender equality paradox” has found its way into those streams of popular culture that tend to be more enthusiastic about evolutionary explanations. An unexpected but robust empirical finding that undermines the more extreme nurturist position on how sex/gender differences arise is the kind of result that gets quoted on television, podcasts, and forums.

Not so fast

A study published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (known by researchers as PNAS) has called into question the strength of the pattern, and especially its more enthusiastic interpretations. Psychologists Mathias Berggren and Robin Bergh, from Uppsala University in Sweden, reanalysed the data from six prominent studies claiming to find the gender equality paradox, including those by Schmitt, and Falk and Hermle.

Their reanalysis hinges on a well-known problem with analyses of correlations among countries (or states, or cities): the fact that the data points are seldom independent. Countries adjacent to each other are likely to be more similar to one another in multiple traits. This can amplify a weak correlation, making it look like a strong one.

More than that, cultural and historic differences between clusters of countries can create an association between traits in one direction, while the associations within clusters can run in the opposite direction entirely. This insight is known as Simpson’s paradox, because associations at one level (between clusters) can obscure or even reverse associations at another level (within clusters).

The top three panels of the figure below, reproduced from the PNAS paper, shows hypothetical patterns within- and between clusters. The center and right hand panels show Simpson’s Paradox effects.

Taking a closer look at the six studies they reanalysed, as well as another data set from the European Social Survey, Berggeen and Bergh found that both gender equality and sex differences were greatest in Western countries, particularly those that speak Germanic languages (which include both English and American) and have a mainly Protestant religious (recent) history. They also argue that the questions and games used to measure both preferences and gender equality were predominantly developed in those countries, and were more likely to pick up subtle variation (including sex differences) in those cultural contexts.

The possibility of Simpson’s paradox does not mean one’s data is useless, but rather it illustrates one of the many potential pitfalls in interpreting correlations. As mathematician Jordan Ellenberg points out, the lesson from Simpson's paradox "isn't really to tell us which viewpoint to take but to insist that we keep both the parts and the whole in mind at once."

It is generally a good idea, and especially so with comparisons across cultures, to not rest all one’s conclusions on a single type of data and level of analysis. The studies that first drew attention the the Gender Equality Paradox were thorough in the range of measures they used, but they relied only on cross-national or cross-cultural comparisons. Other kinds of test, including tracking changes within countries over time, and direct experimental tests, are now needed.

Berggren and Bergh have already begun that work. In the bottom two panels of their Figure 1, reproduced above, they show that a positive association among countries between gender equality and sex differences (in this case the tendency for more men than women to study STEM subjects at university) is challenged by tracking the same measures over time within countries. In the USA, gaps in STEM participation have narrowed as gender equality advanced between 1966 and 2021. That’s the opposite of what we might expect under the Gender Equality Paradox.

Only just getting started

There is much more to the study of how sex differences are shaped by local cultural and economic conditions, including, but by no means limited to, gender equality. I have only given the briefest of introductions to Berggren and Bergh’s paper and the careful way they address the cross-country comparisons that produced such a surprising – perhaps paradoxical – result.

From a researcher’s point of view this is an exciting development. Looking at old data in a new way can advance understanding and lead to better ways of doing science. In this case it can lead to clearer answers to an important question:

What happens to individuals when gender gaps narrow, or when they get bigger?

The political implications of the new paper are likely to be huge. As the gender equality paradox infiltrated public discourse, it has often been welcomed by those social conservatives who embrace biological explanations for human behaviour. It has likewise caused headaches for those most invested in a strong nurturist view of behaviour, and especially sex differences.

Last-wall thinking is never the only option. My own excitement about the paradox, evident in my 2016 article about David Schmitt’s original study, came from the surprise that such an apparently strong pattern could add a new wrinkle of complexity to what it means to be human. I think this is echoed in the enthusiasm of many genuine liberals, curious about the idea that gender equality (or any other trend for that matter) might deliver a range of outcomes, some salutary and others detrimental to individuals.

The idea that “the gender-equality paradox primarily results from cultural differences and data quality rather than gender equality itself”, as Matthias Berggren pithily summed up his paper’s main conclusion, has not yet made its way into the traditional, informal, or social media. Or, as we used to say as scatological schoolchildren in my African childhood, the manure has not yet hit the windmill.

But I don’t think the relative silence will last, the seven posts linking to the original paper on X are outnumbered by 125 on Bluesky, and I would not be surprised if I learned that is because the polarisation of those two channels means Bluesky users are far more likely to find the message consistent with their own convictions.

It would disappoint me, but by no means surprise me, if the new paper were taken as a reason for those invested in social roles and who fear to venture beyond the nurturist side of the Last Wall, to resume normal pre-2016 programming. If that paper has taught us anything it is that no piece of research can be taken as the last word, especially where the relationships between gender equality and sex differences are involved.

One must ask: what's a cis woman to do? The more equality she strives for, the less likely she is to find a male partner who is her equal. "For example, women tend to score higher than men on personality tests for extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Gender equity tends to elevate all three of these traits, but it does so more in women, widening the average sex difference."