People have always used tools to help them think. And they have always fretted about the consequences.

Thoughts on Andy Clark's "Extending minds with Generative AI"

The Internet, smartphones, chatbots, and now generative AI have made it possible to do so much more with our minds than was possible mere decades ago. Or, at the very least, to do similar things far more quickly. Has the invention and spread of those devices changed how we think, or even how we think of what it is to be human?

This is just the latest formulation of an older and far bigger question. In 1998, Andy Clark and David J. Chalmers asked ‘Where does the mind stop and the rest of the world begin?’ Rather than thinking of the mind as merely the brain, they encouraged readers to consider bodies, together with objects and tools we use in thinking, as extensions of our minds.

Many of us are so used to thinking of the mind as the brain that we haven’t stopped to consider whether there are differences between, say, counting in our imaginations, with fingers, with pebbles, or by tallying on pieces of paper. The ‘Extended Mind Thesis’ - that the mind is not confined to the brain but includes the body and some parts of the physical world beyond the body – has proved an incredibly fruitful idea. The original paper is cited by almost 10,000 academic works, a number that many researchers would be happy to achieve in a lifetime’s work. And EMT has spawned popular books and extensive media coverage.

This moment we are having, with ChatGPT, and Claude, and Grok, and Replika, and with other less famous Large Language Models and less popular virtual friends, and with AI in general, has made questions about extended minds all the more salient. Even before we get to the trippier questions like “Where do I stop and ChatGPT begin?” (a question best not asked of an LLM, you have been warned).

Generative AI and Mind Extension

If your media feeds are anything like mine, you might be ready to conclude that Generative AI portends a bleak future. Is the spark of human intellect growing dimmer, the fonts of creativity subsiding to a swamp of marshy homogeny, with human intellect circling the drain?

I was delighted to receive a copy of Andy Clark’s recent Nature Communications commentary on “Extending Minds with Generative AI”. He opens by setting it against just this kind of pessimism that pervades my social media.

Sometimes, it seems like the world is full of techno-gloom. There is a fear that new technologies are making us stupid. GPS apps are shrinking our hippocampus (or in other ways eroding our unaided navigational abilities); easy online search is making us think we know (unaided) more than we do; multitasking with streaming media is driving down our native attention span and (possibly) affecting grey matter density in anterior cingulate cortex

According to Clark, much of the thinking and writing about these effects begins in “entirely the wrong place” by thinking of human minds as only our biological brains. Instead, he argues that this is exactly the kind of discussion that can benefit understanding that humans “are and always have been … ‘extended minds’ – hybrid thinking systems defined (and constantly re-defined) across a rich mosaic of resources only some of which are housed in the biological brain.”

The article, which I recommend in its entirety, reminds us that generative AIs are merely the latest in a very long technological pedigree. Our brains will draw on whatever outside tools they can find and, with the help of our bodies, use them to achieve our goals. Writing, drawing, and building may be more ancient than emailing or setting an AI agent to work building a new customer-management system, but they are all ways that we get things done. “What (the brain) specialises in is learning how to use embodied action to make the most of our (now mostly human-built) worlds.”

Old worries about new technologies

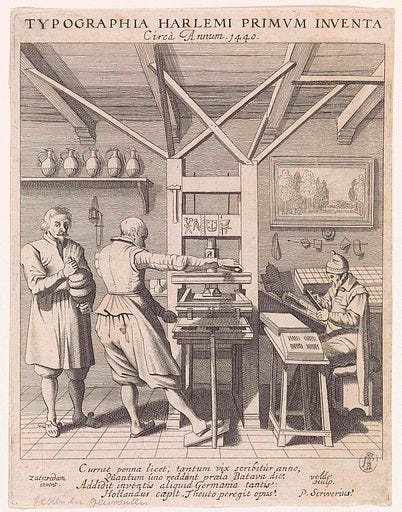

Worrying about the effects of mind-extending technologies on cognitive performance is as old as the technologies themselves. As Clark points out, nearly 2500 years ago Plato articulated, in writing, concerns of the day that relying on writing things down to read later would erode memory and thus undermine intelligence. Similar worries have accompanied other major developments, from the printing press to the personal computer. And then, we have Nicholas Carr asking, in The Atlantic, “Is Google making Us Stupid?”

Those who worried about the effects of new technologies on human cognitive capacities were not wrong. At least not entirely. But they repeatedly underestimated the capacity for human intelligence to readjust and to recruit the next new tool to do more with roughly the same brainpower. According to Clark, the reason we continue to worry about new technologies undermining our intelligence is that, at the root of every worry, sits a “deeply mistaken cognitive self-image”. That is, a failure to recognise that “it is our bedrock human nature to spread the load in this way – to become what I have called ‘natural-born cyborgs’”.

Don’t panic?

Understanding Large Language Models and other AIs as the latest mind-extending innovations gives us reason to think more calmly about implications. But it doesn’t wave away every reason to worry. For one thing, the new technologies are, in their own ways, supremely powerful. They have learned on vast deposits of data about humans and their thoughts. Incredible amounts of computing power and money propel them forward. And, perhaps most important, they support more than memory and computation. They are deeply involved in reasoning, arguing, creating, and taking action in the world. We might be tempted to ask “where does the world stop and Artificial Intelligence begin?”

The great value of Clark’s article is neither in tempering worries about AI, nor in drawing attention to the relevance of thinking of them as mind-extensions. Instead, it is in the way he navigates between the poles of reflexive pessimism and equally reflexive optimism, considering the particular respects in which an extended-mind approach can help us understand how AI interacts with humans, and thus the benefits and the likely pitfalls that could open up on the road ahead.

Here, the devil will (for some time at least) remain in the details. But there is suggestive evidence that what we are mostly seeing are alterations to the human-involving creative process rather than simple replacements. For example, a study of human Go players revealed increasing novelty in human-generated moves following the emergence of ‘superhuman AI Go strategies’. Importantly, that novelty did not consist merely in repeating the innovative moves discovered by the AIs. The same will be true, I conjecture, in domains ranging from art and music to architecture and medical science. Instead of replacing human thought, the AIs will become part of the process of culturally evolving cognition. There, the relative alienness of the AIs thinking will sometimes work in our collective favor, enabling us to see beyond some of the prejudices and blind spots that have been hiding important new ways of thinking. However, the opposite effect can also occur, as noted (in the case of some bodies of scientific research) in another recent study. That study alerts us to the potential role of AI in cementing certain tools, views, and methodologies in place, thus impeding the emergence of alternative approaches – much as, to borrow the authors’ metaphor, an agricultural monoculture improves efficiency while making the crop more vulnerable to pests and diseases.

The nature of AI, notably its signature capacity to change itself, does give us more to keep an eye on beyond what the technologies are currently doing. How will they change, as they learn, as people adapt to the effects the technologies are imposing on their lives, and as the incentives of those humans and corporations that make the technologies shift?

Regular readers will recognise these worries. While I am, in principle, keen to balance optimism and pessimism about technology, it is the latter that often makes for more juicy analysis. Like comparing conversational AIs with sociopaths. Or suggesting that the relationships between users and smartphones bear similarities with those between hosts and their parasites. But I wouldn’t be here, grappling with questions about new technologies and how they interact with our evolved psychology, if I didn’t think those technologies could provide the most important new positive developments in our social and economic worlds.

The reason I received Andy Clark’s paper when I did is that he sent it to me. He had read the academic paper comparing smartphones with parasites that philosopher Rachael Brown and I published in early 2025. The paper builds from the work of Clark, Chalmers, and others about the mind-extending work that smartphones do. Even though smartphones, including all the apps that one might install on them, stack up well as mind-extensions, they can be more.

The capacity of smarphone-based apps to capture and hold attention, in the interests of “freemium” upsellers and advertisers, is a feature, not a bug. As those interests shift, the benefits to users of owning and using a smartphone can shift from net positive to net negative. This kind of shift is seen often in animal evolution, where a mutualistic relationship that benefits interacting individuals of two species can shift to a parasitic one in which individuals of one species benefit, at the expense of individuals of another.

This is a direction I would like to see explored further by those who, like Clark, think about mind-extending technologies. Given the kind words Clark had for Rachael and I about our paper, I think they might. As will I. I think Clark and Chalmers’ ideas present some of the most important tools available as we come to understand the new AI-rich world we inhabit.

Are humans getting dumber? Despite the limited slice of political life and entertainment that I encounter, which leans heavily toward an affirmative answer, I don’t think so. At least not on the year-to-year scale of our own lives. (In evolutionary terms I am not so sure).

Clark doesn’t think so either. I will leave him the last word.

As our tools and technologies have progressed, we have been able to probe ever further and deeper into the mysteries of life and matter. We have come to understand much about the likely conditions at the very start of time and unlocked the biochemical foundations of life. We have not achieved this by becoming dumber and dumber brains but by becoming smarter and smarter hybrid thinking systems.

How You Can Help

Natural History of the Future is free to read, and will remain so for the forseeable future. That includes the fortnightly Artificial Intimacy News. If you find my work interesting or entertaining, you can support it in the following ways.

Subscribe – for free – to get posts sent to you as soon as I publish.

Like and Restack - Click the “Share” button to improve this post’s visibility.

Share the link on social media or send it to a friend via email or messaging app.

Recommend Natural History of the Present to your readers.