Artificial Intimacy News #2

A field report from the place where 21st Century technology meets human social and sexual behaviour.

In this second issue:

What do people mean by ‘artificial intimacy’? What do I mean?

AI bots to help make online dating and flirting easier, better, more successful.

Are companion bots redefining love?

How AI will alter human evolution.

Is machine learning going to kill the ASMR star?

Explainer - What I mean when I talk about “Artificial Intimacy”?

In the previous edition of Artificial Intimacy News, I asked who coined the term “Artificial Intimacy”. My conclusion: not quite sure, but the term has been kicking around – in the context of technology and sex – since at least 2010.

The term is – in the words of Jacobim Mugatu – “so hot right now”, and it is used in a variety of overlapping ways.

For some, like therapist and celebrity author Esther Perel, it is really about the intimacy. “Artificial” is used in a sense of manufactured-and-therefore-never-good-enough.

When I wrote the book on Artificial Intimacy, I wasn’t interested in imposing my ideas of how a fast-moving and quite alien suite of technologies ought to play out as much as I was in documenting the early stages of a remarkable technologic florescence.

So I took a very broad view. And I used the term “artificial intimacies” to denote technologies themselves (rather than just what they do or evoke). Any technology that taps into human social behaviour is a potential artificial intimacy.

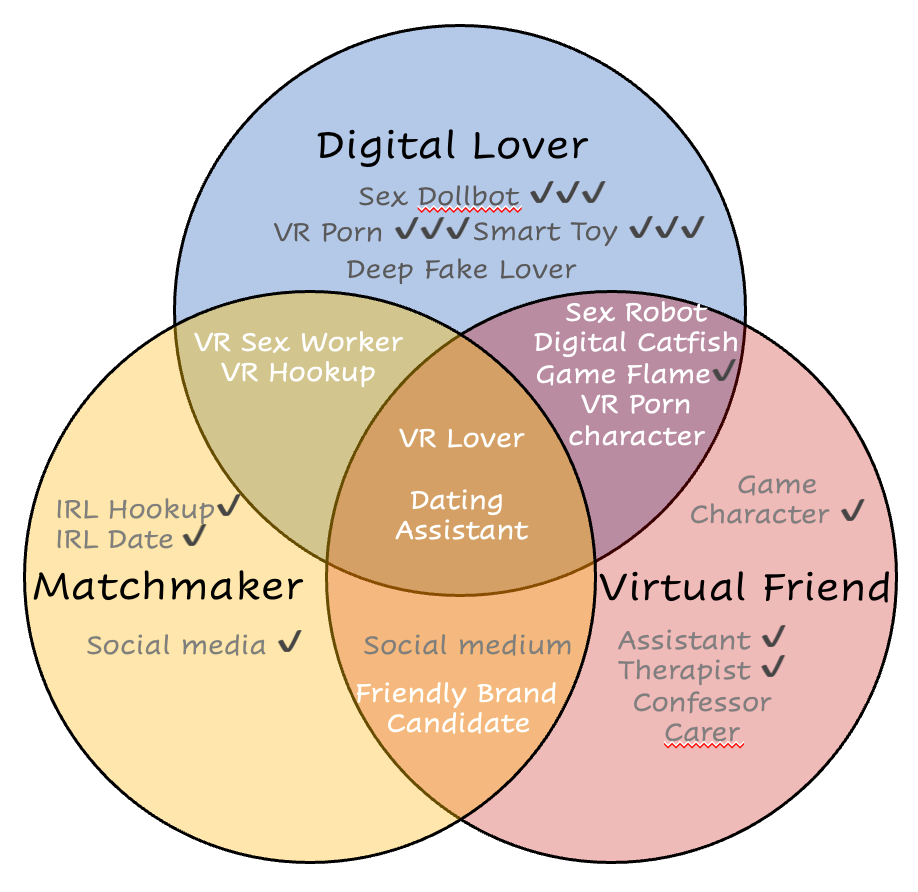

The Venn diagram below shows the three overlapping strands of artificial intimacies that I could discern when writing the book. Those strands also form the sub-heading of the book: digital lovers, virtual friends, and algorithmic matchmakers. The smaller white or grey writing names some technologies already in place at the time (ticked) or envisioned in the book. Were I to redraw this figure there would be far more technologies listed, and many more ticks. Such has been progress in recent years.

Like any formidable troika, the three circles of artificial intimacy bring different strengths. Algorithmic matchmakers are very much here already, learning from our behaviour how to set us up with dates, reconnect us with friends, or even pair us with media. YouTube and Netflix could fit into this group too.

Digital lovers are the flashy, sex-soaked public face of artificial intimacy. The sex dolls that seem perennially on the cusp of becoming convincing sex robots. The VR lovers so convincing we could fall for them.

But it is virtual friends that have outshone the others, especially since large language models burst onto the scene and made conversational AI so much more convincing and seamless than ever.

Artificial Intimacy is an expanding universe (or should the metaphor be ‘ecosystem’?) and I encourage others to see it this way.

Headlines

AI ‘dating wingman’ bots

Look at the figure in the Explainer above. See the sweet spot where virtual friends, digital lovers and algorithmic matchmakers overlap? In that overlap exists all manner of potential for AI dating assistants who can not only make you a match, but facilitate that match by helping you prepare to meet that singular, unique match. An early candidate: the ‘AI wingman’ is already in the air, ready to help you tailor your profile and flirt, baby, flirt.

When Your Therapist Is an Algorithm: Risks of AI Counseling

Artificially Intelligent counsellors were already a thing before the wave of LLM’s revolutionised conversational tech. Indeed the most famous early chatbot, in the 1960’s, ran a therapist script (the kind of therapist that asks open-ended questions and then charges you a mint for the privilege). Here is a Psychology Today article about the current state of that dark art, and its attendant perils.

Teenagers turning to AI companions are redefining love as easy, unconditional and always there

Will virtual friends turn us all into narcissists, eroding any vestige of emotional resilience? That’s a common worry. This article in The Conversation by Anna Mae Duane articulates these fears and presents a variety of strands of evidence that the worries are coming to pass.

As Duane puts it, “the AI companion market has transformed what other applications might consider a bug – AI’s tendency toward sycophancy – into its most appealing feature”.

As a gem of a reminder that not everything shiny is new, Duane also points out that, in the 17th and 18th Century, amid changing views of what marriage was for, “the relatively new pastime of novel-reading was considered dangerous for young people. Concerned elders like the philanthropist Hannah More warned that stories would change how women would respond to romantic advances. Novels, she warned in 1799, ‘feed habits of improper indulgence, and nourish a vain and visionary indolence, which lays the mind open to error and the heart to seduction’.”

What I have been up to….

I recorded a couple of podcasts and was interviewed by two journalists in the two weeks since the last newsletter, but none of those have been published yet. Here are two Substack posts you may have missed.

That’s it for issue #2. I would love to know more about what readers want from this newsletter.

Please use the comments facility below send your thoughts, corrections to my inevitable errors, and links to news stories and relevant Substacks. Or if you prefer, you could restack this newsletter.